Before I left for a semester in Paris, I read Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables in its entirety. I was blown away by the powerful story: suspense, drama, and such insight into the human condition. After gaining an intimate connection with his work, I visited Hugo’s home and felt it was unlike any house museum I’d ever visited. Too many house museums depict history in a detached sense, as a place where some wealthy statesman retreated from the world and his work. Historic homes for artists and writers, however, are usually known as sites of work and action, a place where magic happens.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) was a prominent French author who helped to define the romantic era novel. His works have been famously reinterpreted in film, architecture, and broadway musicals, and two of his homes are now museums. Hugo’s Paris home is the glorious Place Des Vosges, a beautifully symmetrical square of seventeenth century apartments encircling a park. When he lived here, Hugo looked out over a piece of Paris that was far removed from the poverty depicted in Les Miserables. His life never held the financial hardship his fiction depicts, but he did experience his share of turmoil.

Hugo was forced to leave this palatial home halfway through his career. Because of his politically radical views, Hugo was once deemed a danger to the nation and was banished from France. His staunch republicanism became quite controversial after the rise of a new emperor in the 1850s. Once Napoleon III was forced from power in 1870, Hugo returned a hero. Although he didn’t live in this house consistently, the home includes artifacts from throughout his life.

The simple entryway’s walls of white marble are decorated with paintings of Hugo’s youth and his family. In the center of the room hangs a young woman’s dress. It’s wall label describes one of Hugo’s most heartbreaking experiences. In 1843, his eldest daughter Leopoldine drowned in the Seine when she was only 19. Hugo wrote many early poems about this tragedy, and undoubtedly drew on the experience throughout his career.

Unlike the white of the first room, the next space is robed in red velvet, from the tactile wallpaper to the voluptuous curtains. As Hugo’s career took off, his decor seems to have become more elaborate. In the early years, he supported the monarchy, and the baroque furniture here seems drawn straight from King Louis Philippe’s sitting room. Hugo welcomed artists like Dumas, Lamartine, and Gautier to salon conversations in this room. Some of his more radical guests would eventually persuade his political views and his shift away from supporting the king to republican nationalism.

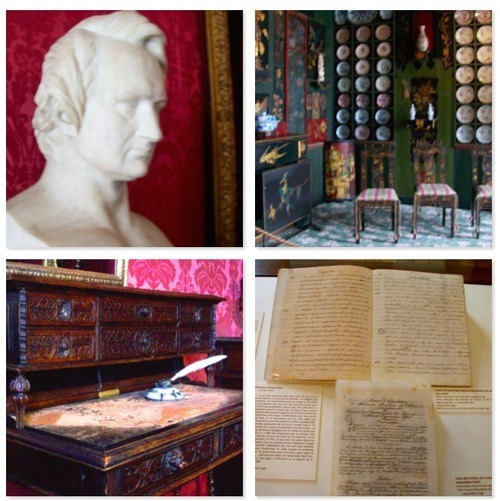

The dark gothic style of the next two rooms symbolizes this shift, with heavy wooden furniture around a medieval dining room table, split-paned glass windows, and an ornate four-poster bed amid ancient tapestries. It is here that visitors remember Hugo’s role in reviving artistic appreciation for gothic art. Through his famous novel, Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), Parisians saw their crumbling architecture through new eyes, for Hugo’s main character was the Notre Dame cathedral itself. Shortly after publication, Parisians rallied to renovate the iconic flying buttresses, gargoyles, and stained glass windows, which today comprise one of the most visited places in the world.

One sitting room really stood out for me. It is decorated entirely in Asian art: carved wood, delicate china, and gilt paintings. In Hugo’s time, as globalization and European empires brought art from the other side of the world, the exotic style became quite fashionable. In the face of these global “others” European artists were inspired to look inward and explore their own local culture, like Hugo’s interest in Parisian medieval art. Nationalism was both a political and an artistic theme in the Romantic era: Hugo’s Asian room portrays a fascinating foil to his francophone literary voice.

One of the most powerful pieces on display is not immediately evident. Indeed, many visitors often walk right past it. Next to a window, standing chest-high, is the artifact Hugo used the most: his writing desk. He preferred to stand while he wrote, an odd quirk that somehow makes his writing process more visceral. Visitors can see early drafts of his writing and desk’s rough surface and imagine themselves standing there in the place of Hugo himself. The magic of the artist’s home comes from seeing the humanity behind the brilliance, a reminder that any one of us is capable of creating something extraordinary.

No comments:

Post a Comment