In our world of rules, the art of René Magritte questions everything: love and language, right and wrong, and the nature of truth and illusion. Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938 at the Art Institute of Chicago is on display from June 24 to October 13, 2014. Although Magritte’s work asks us to question conformity, the art itself is posed in stark contrast to the realities of crowd control in a large public museum. The restricted exhibition layout and overzealous security guards impose an institutional authority that expects visitors to follow museum standards even as the art rejects such expectations.

Magritte’s fame is immediately visible as I approach the gallery - the line goes out the door. Only small groups are allowed to enter at a time, in order to keep the crowds manageable. After a 15-minute wait, I enter with my group. Someone near the front notices the introductory wall label, inspiring the whole group to stop and read. Magritte, we read, wanted to “overthrow the oppressive rationalism of bourgeois society,” and yet here we are, ironically corralled into mimicking a herd of strangers.

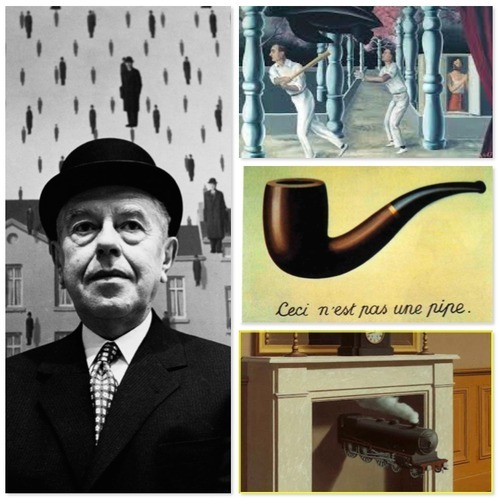

The first several rooms are tight for the sizable crowd. The works in these rooms evince some of the artistic symbols Magritte was most fond of: bilboquets, bowler hats, and clouds. In one painting, two men are playing baseball, but oddly, they’re looking off in the same direction. I think about the arbitrary nature of sports rules: if we try it facing the other way, is it still baseball? As I wonder, a security guard approaches the woman next to me and tells her she must wear her backpack over her chest. Although my first thought was that perhaps a passionate curator wanted to give visitors a physical sense of backwardness to match the painting, I soon decide it’s probably meant to deter theft and facilitate crowd movement.

We wind along in a line, sometimes into tight corners with little space fo th double row of traffic. One hallway has two of the exhibit’s most disconcerting paintings. In the left painting is a girl biting into a bird, which was inspired by Magritte’s memory of his girlfriend eating candy. The painting on the right was inspired by repetitive wallpaper design, and here rows of half-masticated birds continue the themes of the previous painting. Visitors who are stuck next to these pieces look visibly disturbed, but traffic is caught, waiting to enter the cramped room that follows. I can’t help but wonder if this was unfortunate exhibit design, or a conscious effort on the curators’ part to upset the bourgeois visitor by forcing us to confront our own carnivorous human nature.

In the second section’s works, we see Magritte starting to play with language. A few paintings seem like simple word-association tests at first, until viewers read closer. “Sky” is written below an image of a briefcase, “table” below a leaf, and “sponge” below a sponge. An excellent wall label makes sense of this nonsense: “Magritte reminds visitors of the arbitrariness of language and meaning. Even in the case where the word and image are the same, neither of course is a real sponge.” This theme leads to one of his most famous pieces, The Treachery of Imagery. The words across the bottom, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” remind us that the image above is not a real pipe at all, but only a painting of a pipe.

Looking to a following room, I see a crowded bench and realize how little seating I’ve seen throughout this exhibit. Visitors are not invited to take time and ponder, but encouraged to keep moving, like an assembly line for art appreciation. I wonder what Magritte would have thought. Fortunately, the later rooms of the exhibit are significantly more spacious than the first rooms. A long hall hung paintings on the same side of 12 walls, standing in a row down the middle, like a line of dominoes. Each painting finally had sufficient space for viewing, and ample room for passing by on either side.

The last painting on display is called Time Transfixed. This large painting depicts a fireplace from a seemingly ordinary room. A mirror and a clock hang over the mantlepiece, but coming out of the hearth is a train. As a woman next to me leans close to read the label, a security guard in the corner coughs loudly. The woman turns and he shakes his head emphatically, reminding her not to get too close, to follow museum etiquette. I’d almost gotten lost in the art again, but museum regulation brought me back to the real world. Looking at the clock on the mantle, I’m reminded to check my own watch before leaving, in order to catch the next train on time. Maybe next time I’ll overthrow rationalism.